“The artist must remain faithful to himself and to his national roots.” - Alphonse Mucha

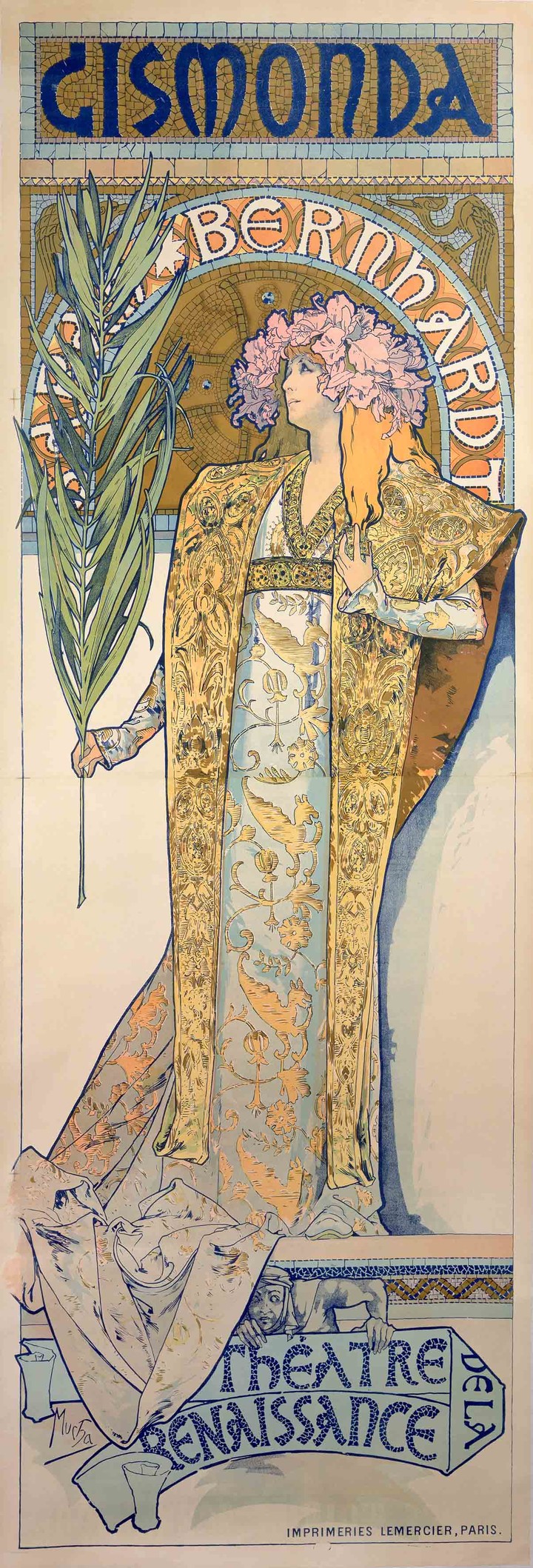

This section looks at Mucha’s beginnings as a “bohemian”, an outsider of the French establishment (“Bohemians" also means exotic people from the Czech regions), and how this “exotic” artist made an extraordinary breakthrough with the single poster Gismonda, designed for Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923). The display features examples of his illustrations as well as early drawings that demonstrate his solid academic training, followed by a series of his posters for Sarah Bernhardt and other works associated with her.

“I prefer to be someone who makes pictures for people, rather than who creates art for art’s sake.” - Alphonse Mucha

This section looks at Mucha’s approach to poster design and how he established his distinctive style, famously known as “le style Mucha”, through examples of his advertising posters and decorative panels. The display also features Documents décoratifs (1902) – a ready-to-use “design hand book” for and manufacturers to “contribute towards bringing aesthetic values into the arts and crafts.”

“My art, if I may call it that, crystallised. It was en vogue. It spread to factories and workshops under the name of ‘le style Mucha’”. - Alphonse Mucha

Looking at Mucha’s ascend to a celebrity artist against the backdrop of the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1900, this section features Mucha’s works associated with the Exposition as well as his collaboration with celebrated Parisian jeweller Georges Fouquet (1862-1957). Also shown here are the works produced in America, especially those demonstrating Mucha’s close association with the theatre world, such as the decoration of the German Theatre in New York and posters for American actresses, Leslie Carter (1857-1937) and Maude Adams (1872-1953).

“Art is the expression of innermost feelings…a spiritual need.” - Alphonse Mucha

This section explores the influences of Mucha’s Spiritualism and Masonic philosophy on his work, which is particularly reflected on his illustrated book Le Pater. Published in 1899, the book was Mucha’s message to future generations about the progress of mankind – the way for man to reach a Universal Truth – through the words of the Lord’s Prayer with illustrations inspired by Masonic symbolism. Also featured here are Mucha’s expressionistic pastel drawings, which were produced privately and never exhibited or published in his lifetime.

“The mission of art is to express each nation’s aesthetic values in accordance with the beauty of its soul. The mission of the artist is to teach people to love that beauty.” - Alphonse Mucha

This section portrays Mucha as a patriot through a variety of the works he produced for his homeland before and after its independence. Highlighting The Slav Epic in particular, the section also looks at how he created this complex monumental work through the variety of preparatory works – from large-scale and small-scale studies to studio and documentary photographs.

“The purpose of my work was never to destroy but to construct, to link, because we all must hope that humanity will draw closer together and this will be easier the more they understand each other.” - Alphonse Mucha

Portraying Mucha as a philosopher, this section looks at his works expressing his humanitarian concerns and his response to the threats of war in a rapidly changing world. The exhibition ends with Mucha’s final project for a monument for the entirety of mankind: a triptych depicting The Age of Reason, The Age of Wisdom and The Age of Love. Begun in 1936, when the terrible reality of war was approaching day by day, Mucha wished to depict Reason, Wisdom and Love as the three key attributes of humanity, believing that only the harmonious working of the three elements would contribute to the progress of mankind. Although Mucha was unable to realise this project, the surviving studies convey his universal message for peace to us today.